Opinion: Fourth Amendment Waivers Are Unconscionable

The views expressed in this opinion piece are those of the writer only. They are not necessarily the views of the law firm or any of its attorneys.

Protecting the constitutional rights of a client is a task that criminal defense attorneys take very seriously. As such, when a client is asked to waive any right as part of a disposition of his or her criminal case, the client needs to fully understand what the implication of the waiver is.

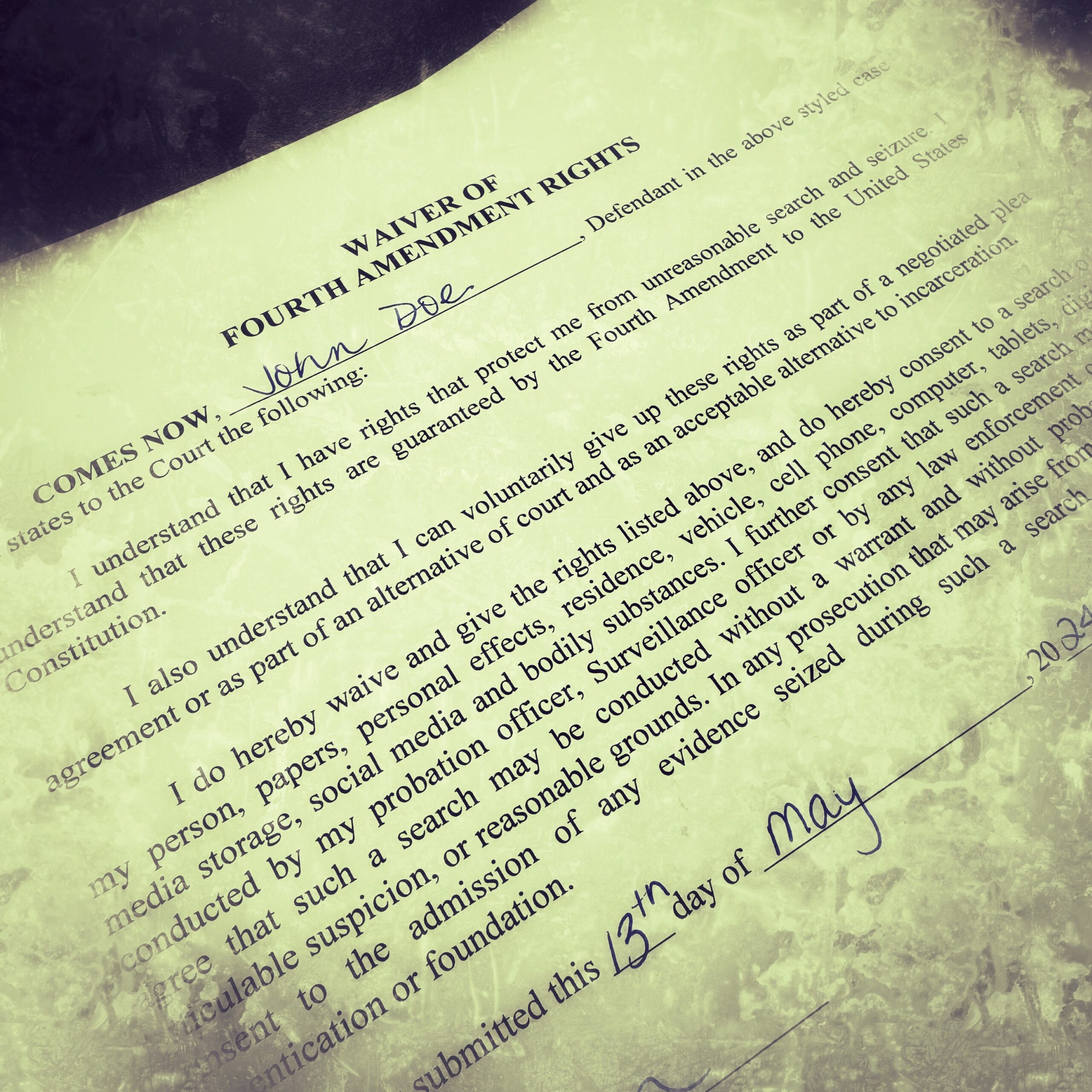

In some states, criminal defendants are strong-armed into waiving their Fourth Amendment rights as part of a plea bargain. What is shocking is that these waivers last, in some cases, for years past when the individual has finished his or her sentence. Such waivers are unconscionable and have no place in a fair and just legal system.

The Fourth Amendment in General

In the United States, the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution reads:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

There is a large volume of law relating to this Amendment. But boiling it all down, in very simple terms this means that law enforcement cannot just search you, your car or belongings, or your home on a whim. Additionally, each state has its own provision in its state constitution relating to searches.

How Criminal Defendants Can Waive or Lose Their Constitutional Rights

When someone has a case pending in the criminal legal system, their constitutional rights come into play. During plea negotiations, a defendant may give up certain rights in order to obtain a more favorable plea bargain. Here in New York, those rights may include the right to a trial by jury or the right to have the prosecution prove their guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

If a person pleads guilty and receives a sentence of community supervision (such as probation or parole), they have fewer Fourth Amendment protections while serving that sentence. In New York, a person who is serving a sentence of community supervision can have their person, home, or things searched by their probation or parole officer.

For example, a person who is on DWI probation here in Westchester can expect that their probation officer will come to their home and search for alcohol or other intoxicants. However, that doesn’t give the probation officer limitless searching powers. If the probationer were suspected of, for example, a computer crime, the police would likely still need to obtain a warrant to search that computer.

What is a Fourth Amendment Waiver?

In some states, prosecutors are including a Fourth Amendment waiver as a requirement of plea bargains. Specifically, this waiver permits law enforcement to search a person, their car or belongings, and their home for a certain number of years. According to a recent report, some of these waivers can last for as long as 20 years.

This waiver could continue even after they’ve completed their sentence of probation or parole. And the waiver could continue even if there is no proof they’ve committed any crime. For those who’ve entered into such a waiver, they cannot challenge the legality of anything law enforcement finds during these warrantless searches.

In states like Virginia, these waivers are said to be standard in plea bargains. Additionally, there is evidence they are used in other states such as California, Georgia, and Idaho.

Why Fourth Amendment Waivers Are Wrong

If an individual has finished serving their sentence, all of their rights should be restored. We do not need to be living in a society where we have second-class citizens with fewer rights just because in the past they were found guilty of a crime. Indeed, the federal courts have been critical of such Fourth Amendment waivers. In United States v. Scott, the Ninth Circuit held that the government may not conduct a search of an individual released while awaiting trial based on less than probable cause even when his Fourth Amendment rights were waived as a condition of pre-trial release.

Moreover, the waivers exacerbate disparities in a system which already disproportionately impacts people of color and poorer communities. If we continue to allow these waivers, the warrantless searches will then further unequally impact those communities. Also concerning is that there is also no way to track how often the searches pursuant to these waivers are performed.

Further, these waivers do not promote best practices among police. Without such waivers, police must have probable cause to search – and we should continue to hold them to that standard. Additionally, the waivers may be an easy way for police to cover-up bad searches. For example, officers can just go to a database and see if a person signed away their rights. In that case, the defendant won’t be able to challenge the search – even if law enforcement engaged in improper conduct.

References:

- Lauren Gill, “‘An Impossible Choice’: Virginians Asked to Waive Constitutional Rights to Get a Plea Deal,” com (May 9, 2024) https://boltsmag.org/fourth-amendment-waiver-virginia-police-traffic-stops/ (last accessed May 13, 2024).

- Gina M. Muccio, “United States v. Scott: Should a Pre-Trial Releasee Be Subject to Fourth Amendment Searches and Seizures Based on Probable Cause or Reasonable Suspicion?,” 27 Pace L. Rev. 339 (2007). Available at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/plr/vol27/iss2/5/ (last accessed May 13, 2024).

Image: © 2024 Pappalardo & Pappalardo, LLP. All rights reserved.